A Story of Community, Resilience, and Renewal on Tribal Land

What Was Section 14?

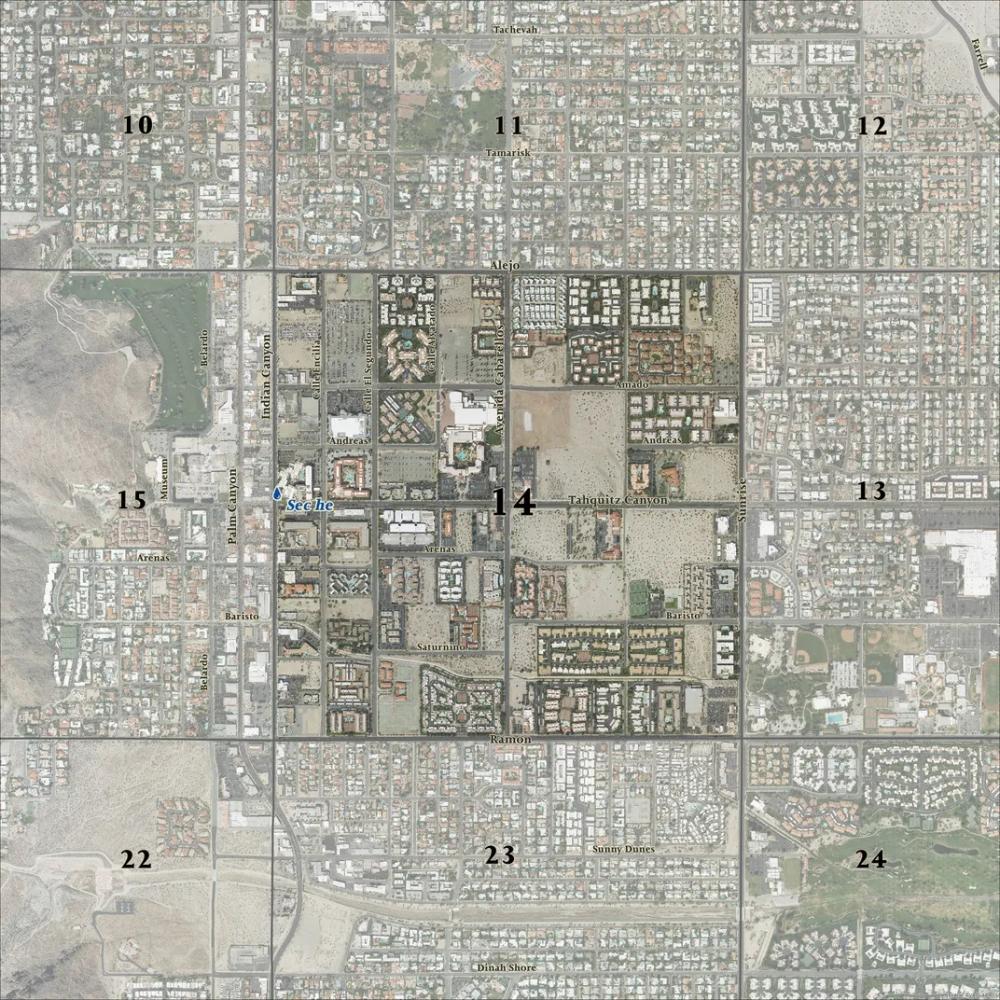

Bordered by Alejo Road (north), Ramon Road (south), Sunrise Way (east), and Indian Canyon Drive (west), Section 14 is part of the checkerboard-shaped Agua Caliente Indian Reservation.

Who Lived in Section 14: A Portrait of Resilience

Despite lacking basic city services like trash collection, paved roads, and plumbing, Section 14 was a vibrant, multicultural neighborhood filled with warmth, creativity, and faith. Families built homes with their own hands, raised children, and formed lifelong bonds in this one-square-mile tract of tribal land. They leased plots from Agua Caliente tribal members and built homes, churches, and businesses.

-

Residents included Black, Latino, Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, and Indigenous families — many of whom worked as gardeners, housekeepers, construction workers, and hospitality staff in Palm Springs’ booming resort industry.

-

Fathers built homes from salvaged materials, often adding rooms as families grew. One survivor recalled her father building her a custom closet because she had to share space with her brothers.

-

Children attended local schools and played in the streets until dark. Neighbors shared meals, watched out for one another, and celebrated holidays together.

-

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) developed their own Religious, Social, and Cultural Institutions on Section 14.

Bethlehem Pentecostal Church of God in Christ was built in 1944 with a city permit.

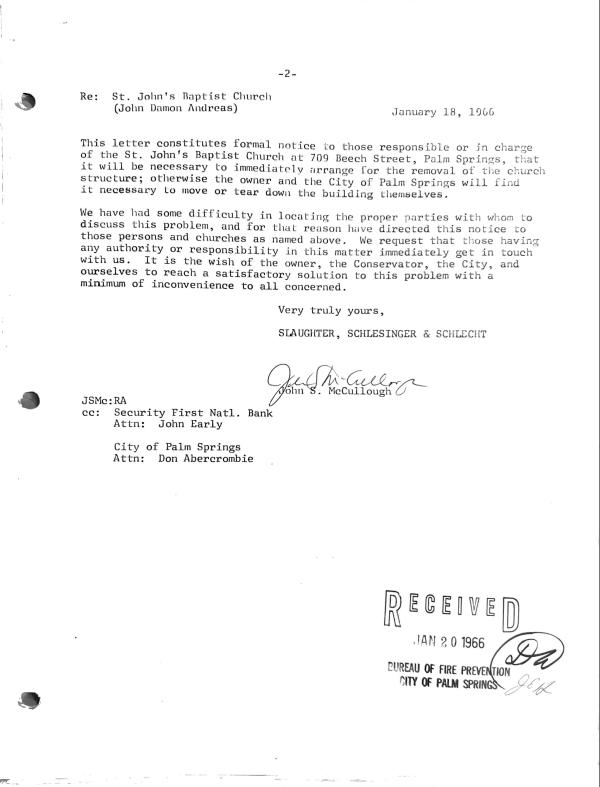

St. John's Baptist Church began in a tent and grew into a 130-seat sanctuary by 1948, complete with a parsonage. Below is part of the letter, which provides the church with formal notice from a law firm stating that the church will be demolished.

Survivors like Pearl Devers and Margaret Godinez-Genera recall homes filled with music, laughter, and a sense of pride. Pearl lived in Section 14 until age 12. She founded the Palm Springs Section 14 survivors group, which now includes over 400 descendants. Margaret spent 28 years of her life in Section 14, where she raised her family. She vividly recalls waking to the smell of smoke and watching bulldozers destroy her neighbors’ homes. Her family fled with only what they could carry.

How the City Became Involved

Palm Springs' involvement with Section 14 began in the 1930s, long before demolition crews arrived. What started as a public health concern evolved into a prolonged and complex effort to remove low-income housing from valuable downtown tribal land.

Early Concerns (1932–1948)

By the early 1930s, state and county health officials began inspecting Section 14 and flagged the area’s substandard living conditions. A 1933 report described severe sanitation issues. In 1948, Riverside County Health Officer Dr. Robert E. Westphal estimated that approximately 1,500 people were living in unsafe structures and called for immediate clean-up and potential condemnation. (Desert Sun, Nov. 12, 1948)

City Pressured to Act (1951–1952)

In 1951, the California Housing Authority and Riverside County formally pressed the City of Palm Springs to address Section 14’s housing issues. Eviction notices were issued, and the City Manager was tasked with planning for displaced residents. Recognizing the lack of low-income alternatives, the City Council voted to delay evictions until May 1952, explicitly noting that removal without relocation would amount to exclusion from the city.

Eviction Delays & Code Enforcement (1952–1953)

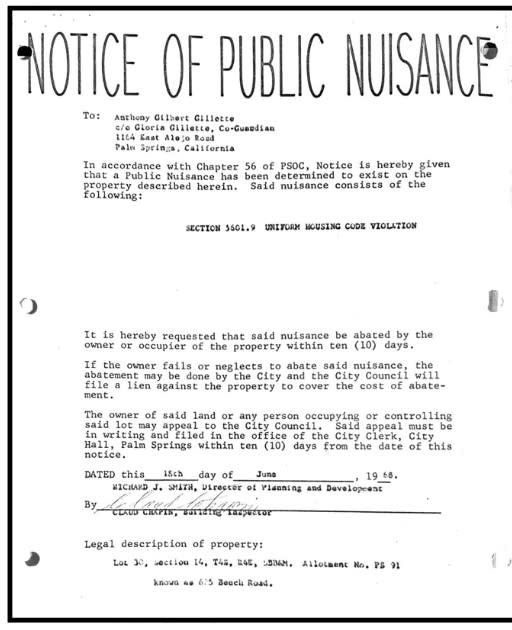

During this period, The Desert Sun reported that the state had quietly approved a delay in demolitions. Meanwhile, the City Council extended eviction deadlines and passed new resolutions. Building inspectors were instructed to notify residents that homes must either be upgraded or removed.

Toward Clearance (1953–1955)

With no affordable housing available, evictions were delayed yet again. Trailer homes were ordered to relocate to designated parks. Formal abatement hearings soon followed, requiring residents to bring their properties up to code or face demolition.

Despite public statements acknowledging the community’s importance and the housing shortage, these administrative steps gradually paved the way for large-scale evictions. While the City’s involvement was originally framed as a health and zoning intervention, it ultimately facilitated displacement, destruction, and loss.

The Eviction & Clearance Process

In the 1950s and 1960s, with tourism and development booming, city officials reimagined Section 14 as future resort land. But they couldn't purchase tribal property outright. Instead, they partnered with federally appointed conservators, who managed the assets of tribal members, often without full disclosure.

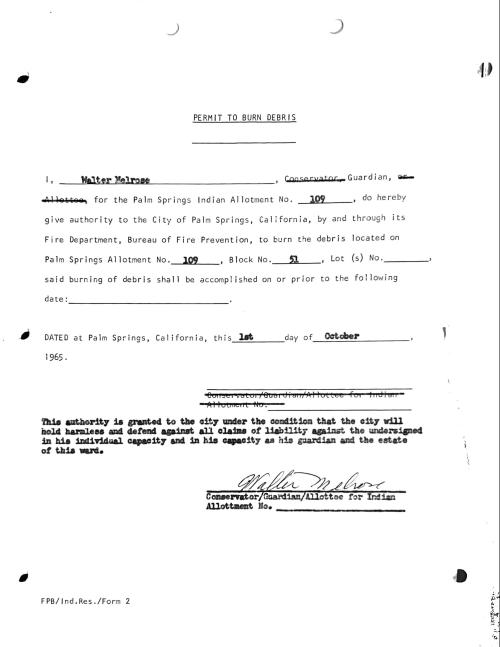

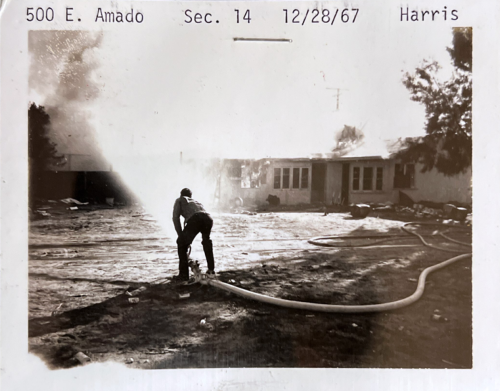

On December 5, 1956, the Palm Springs Fire Department oversaw the first burn, in which ten former trailer homes were incinerated near the Mineral Baths at the intersection of Indian and Tahquitz (now Indian Canyon & Tahquitz Canyon Way). These controlled demolitions, backed by burn permits signed by tribal allottees, conservators, guardians, and buyers, became a disturbing norm.

How Residents Were Notified

- Tribal landowners, guardians, and conservators issued 30-day notices, which were often extended upon request.

- Affidavits were filed as proof of notice.

- Noncompliant tenants faced unlawful detainer hearings.

- The City followed an administrative protocol: tenants could appeal evictions via the Human Relations Commission or Board of Appeals.

Between 1962 and 1969, controlled abatements continued. Tribal landowners were involved in the burn approvals, but the situation was far from straightforward. Between 1962 and 1969, 48 burn permits were issued for demolitions on Section 14. These were signed by a mix of tribal allottees, conservators, guardians, and buyers, indicating that not all permits originated directly from tribal members with full autonomy. Many Agua Caliente landowners were under federal conservatorship, which meant their estates were managed by court-appointed non-Native guardians who could make decisions—including approving demolitions—without full disclosure or consent from the tribal member.

- Deputy sheriffs delivered multi-stage eviction notices.

- Demolitions typically followed tenant removals or the expiration of leases.

- Tribal landowners granted burn permits—some under conservatorship and lacking direct control over their estates.

- 48 burn permits are now archived: signed by 10 conservators, 9 guardians, 6 allottees, and others.

The City's Fire Marshal ensured all homes slated for demolition were vacant, issued press releases, and coordinated burn schedules. A designated Clean Up Coordinator liaised between the City, BIA officials, and tribal representatives. Abatements were framed as legal, sanitary solutions, but for residents, the process felt like erasure.

Tribal Land, Federal Conservatorship & the BIA

The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians owned Section 14; however, federal law limited the control of many members. Through conservatorship programs, tribal estates were managed—often by non-Native guardians.

- The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) helped coordinate abatements, confirming legal procedures and notice delivery.

- In 1965, BIA rep Paul Hand wrote: "To the best of our knowledge, there are no buildings in the area worth saving."

- His memo instructed landlords to issue 30-day notices, log exceptions, and work with the City on phased clearance.

This federal partnership—between the City, BIA, and conservators—legitimized widespread removal while sidelining tribal self-determination.

What the Attorney General Report Said

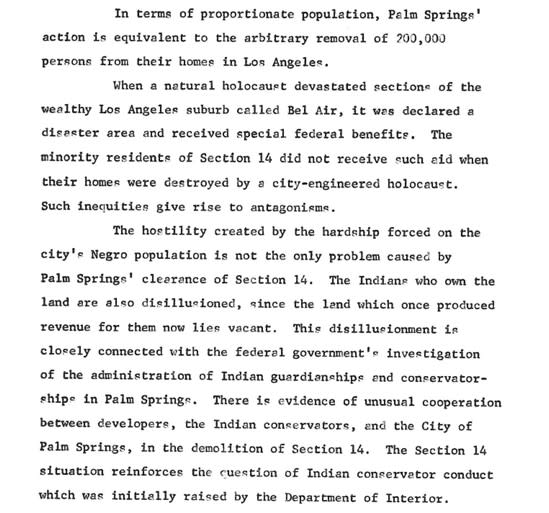

In 1968, the California Attorney General published a report calling the Section 14 clearances a "city-engineered holocaust." Authored by Deputy AG Loren Miller, Jr., the report revealed systemic disregard for residents' humanity.

Yet, the City of Palm Springs disputed its findings, citing court rulings like Leonard v. City of Palm Springs (1968), where a judge upheld demolition with landowner permission. Critics noted that Miller only visited for a single day and overlooked public records showing the City's attempts to defer evictions and address health concerns dating back to 1951.

After the Burn: Redevelopment & Vacancy

After the homes of Section 14 were cleared, much of the land sat vacant for years. But in time, the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians began reclaiming their ancestral space—not just through memory, but through visionary development.

Spa Resort Hotel (demolished) & Casino

-

In 1957, the original bathhouse was demolished. A year later, the Tribe leased eight acres—including the sacred hot mineral spring—to developer Samuel Banowit.

-

The Spa Resort Hotel opened in 1963, designed by midcentury architect William Cody, and quickly became a Palm Springs icon.

-

The Spa Resort Casino (now Agua Caliente Casino Palm Springs), built atop the Tribe’s sacred spring, opened in 1995, marking a new era of tribal enterprise and cultural stewardship.

Tribal Land Policy Shift (1959 - 1968)

In 1959, Congress passed the Indian Leasing Act, allowing tribes like the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians to lease reservation land for up to 99 years—a dramatic shift from the previous five-year cap that had stifled development. Section 14, a one-square-mile tract, suddenly became prime real estate for long-term commercial investment.

Read More: Learn about the all-female tribal council that broke the glass ceiling and secured 99-year leases.

Yet this policy shift didn’t immediately empower tribal members. Many were still under federal conservatorship, a system in which non-Native guardians controlled tribal estates, often making decisions without complete transparency or consent. These conservators could approve leases, terminate tenancies, and even authorize demolitions. Tribal autonomy remained constrained until the conservatorship program was phased out in 1968, following mounting pressure from legal and civil rights activists.

Displacement Ripple Effects (1960s - 1970s)

The clearance of Section 14 displaced hundreds of families, many of whom had lived in the area for decades. With few affordable housing options in Palm Springs—and racial deed restrictions barring Black families from purchasing in many neighborhoods—former residents scattered across the Coachella Valley:

- Banning & Beaumont: Became havens for displaced Black families seeking homeownership.

- Cathedral City & West Garnet: Offered modest housing tracts, though often far from employment centers.

- Dream Homes & Veterans’ Tract: Latino families pooled resources to buy homes in these developments, though access remained unequal.

Some residents commuted back to Palm Springs for work in the hospitality, construction, or domestic labor industries. Others lost not just homes, but community networks, generational wealth, and access to city services.

Vacancy & Unfulfilled Promises (Late 1960s–1970s)

Despite the aggressive clearance campaign, much of Section 14 remained vacant for years. Developers were slow to commit, and lease negotiations dragged, partly due to lingering conservatorship issues and tribal mistrust. The land, stripped of its homes and churches, sat as a scarred void in the heart of Palm Springs.

This period marked a civic paradox: the city had displaced a vibrant community in anticipation of growth, yet the promised transformation stalled. Survivors described the emptiness as a “ghost town,” where memories lingered but no new life took root.

Civic & Commercial Transformation (1980s - 2000s)

By the early 1980s, the cleared land of Section 14 was reimagined as the civic and commercial heart of Palm Springs. The city’s developers saw an opportunity in the vacant tribal parcels adjacent to downtown.

Rise of Luxury Infrastructure

- Palm Springs Convention Center opened in 1984, anchoring the city’s event and conference industry. Built on former residential land, it symbolized the shift from community to commerce.

- Hotels and resorts followed, including expansions of the Spa Resort Hotel (demolished) and later the Agua Caliente Casino Palm Springs, which opened in 1995 atop the Tribe’s sacred hot mineral spring.

- Retail corridors along Indian Canyon Drive and Tahquitz Canyon Way emerged, replacing homes and churches with boutiques, galleries, and restaurants.

This era marked a dual transformation: while the city pursued luxury and leisure, the Tribe reclaimed its role as a civic and cultural force, reshaping Section 14 not just as a commercial zone but as a site of tribal visibility, memory, and renewal.

Explore the tribe's presence through Visit Native Palm Springs

Indian Canyons & Tahquitz Canyon: Sacred hiking trails and ancient artifacts.

These canyons are part of the Agua Caliente reservation and have been home to the Cahuilla people for thousands of years. They're listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Tahquitz Canyon: Known for its seasonal 60-foot waterfall, ancient rock art, and remnants of irrigation systems. The canyon is tied to the legend of Tahquitz, a powerful shaman spirit said to still reside in the area.

Indian Canyons: Includes Palm, Andreas, and Murray Canyons. Visitors encounter house pits, food preparation areas, and ceremonial sites. Palm Canyon hosts the world’s largest California fan palm oasis.

Interpretive Hikes: Ranger-led tours offer insights into traditional uses of native plants, ancient village sites, and tribal stories. These hikes are immersive, blending ecology with oral history.

Visitor Experience: Trails range from easy loops to challenging climbs. The Tahquitz Visitor Center features exhibits, artifacts, and a short film on the canyon’s legend.

The Spa at Séc-he: Healing Waters and Cultural Reverence

Located atop the ancient Agua Caliente Hot Mineral Spring—called Séc-he, meaning “the sound of boiling water”—this site has sustained the Tribe since time immemorial.

Wellness Meets Tradition:

-

Private Mineral Baths: Guests can experience “Taking of the Waters,” a ritual of soaking in magnesium-rich spring water that rises from 1.5 miles underground.

-

Signature Treatments: Therapies incorporate native botanicals, heated quartz, and traditional healing techniques. Float pods, cryotherapy, and halotherapy salt caves enhance the experience.

-

Architecture & Design: The spa’s terrazzo floors and mosaics reflect Cahuilla basket designs and storytelling. It’s a sensory journey through tribal heritage.

Tribal Vision: Chairman Reid D. Milanovich calls the spa a milestone: “We are honored to share some of our most precious rituals with the world.”

Agua Caliente Cultural Museum: A Living Legacy of the Cahuilla People

Located in the heart of downtown on Section 14, the Agua Caliente Cultural Museum is a 48,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art facility dedicated to preserving and sharing the history, art, and traditions of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. It anchors the Agua Caliente Cultural Plaza, which also includes the Spa at Séc-he, the Oasis Trail, and a native plant garden.

-

Permanent Gallery: Divided into five immersive exhibit areas, the gallery begins with the Tribe’s creation story and guides visitors through ancestral lands, ceremonial practices, and archaeological discoveries dating back 8,000 years.

-

Multimedia Storytelling: A 360-degree animation theater, interactive map tables, and first-person video narratives from Tribal members bring history to life.

-

Educational Mission: The museum serves as a cultural resource for Tribal youth and elders, offering programming for the public that includes guided tours, workshops, and speaker series.

-

Architectural Design: Inspired by Cahuilla basketry and desert landscapes, the museum’s design reflects both tradition and innovation.

-

Recognition: Named one of TIME Magazine’s “World’s Greatest Places” in 2024, the museum has welcomed tens of thousands of visitors since its grand opening.

-

Rotating Exhibits: The current exhibit is “Section 14: The Untold Story.”

This powerful installation centers on the forced evictions of Native and nonwhite families from Section 14 in the 1950s–60s. It’s curated with survivor interviews, archival maps, and government documents. A 16-minute documentary features Tribal Elders recounting life on Section 14 and the trauma of displacement. Surrounding displays highlight the Tribe’s fight for sovereignty and cultural preservation. Reid D. Milanovich emphasizes, “This exhibit is actual, true history—facts of what life was like back then.” It runs through May 31, 2026.

Visitor Info: Located at 140 N. Indian Canyon Drive, open Tuesday–Sunday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Admission includes access to the Changing Gallery.

Section 14 Today: Memory & Justice

Modern-day Section 14 includes hotels, resorts, and civic centers. But its past echoes in ongoing restorative efforts:

- In 2024, the Palm Springs City Council approved $5.9 million for verified survivors.

- An additional $21 million in housing and economic equity initiatives is planned.

- A public memorial and Racial Healing Center are in early development.

Section 14 is not just a neighborhood lost — it's a cultural epicenter that has been reclaimed. By visiting its landmarks, listening to its survivors, and learning through tribal initiatives, we build bridges between Palm Springs' glamour and its grassroots.