A Modernist Marvel Finds its Forever Home at the Palm Springs Art Museum

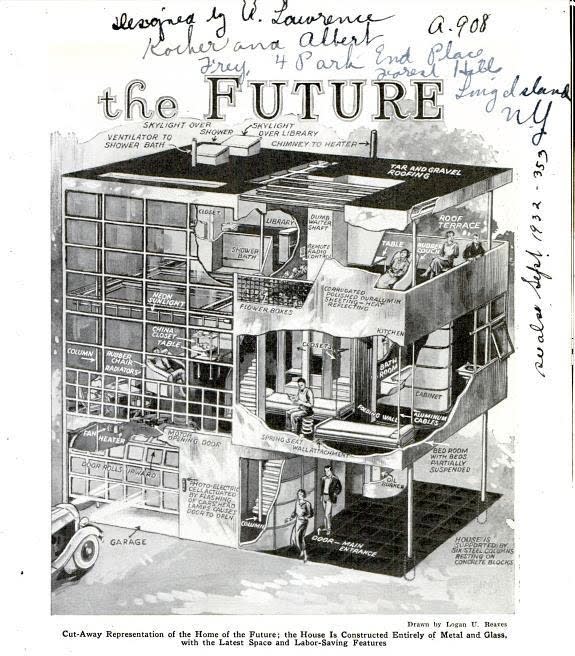

In 1931, the Allied Arts and Industries and the Architectural League of New York unveiled the starkly modern, all-metal 'Aluminaire' home, constructed primarily of aluminum and glass components, which inspired the name. It was intended to be mass-produced and affordable, using inexpensive, off-the-shelf materials. The house caught the public's attention so much that more than 100,000 visitors toured the home in just one week on exhibit. The three-story house was designed by A. Lawrence Kocher, the managing editor of Architectural Record, and Albert Frey, then a 28-year-old Swiss architect who had recently immigrated to America after working in Paris for the great architect Le Corbusier.

It was the first all-metal house constructed in the U.S. and of such importance in the architectural world that images of it were featured in the prestigious exhibition 'The International Style – Architecture Since 1922' at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1932. The house emboldened a new architectural movement in the United States. The Aluminaire was an overt demonstration of bringing together the ideas of mass production and high-density community planning.

The House Design

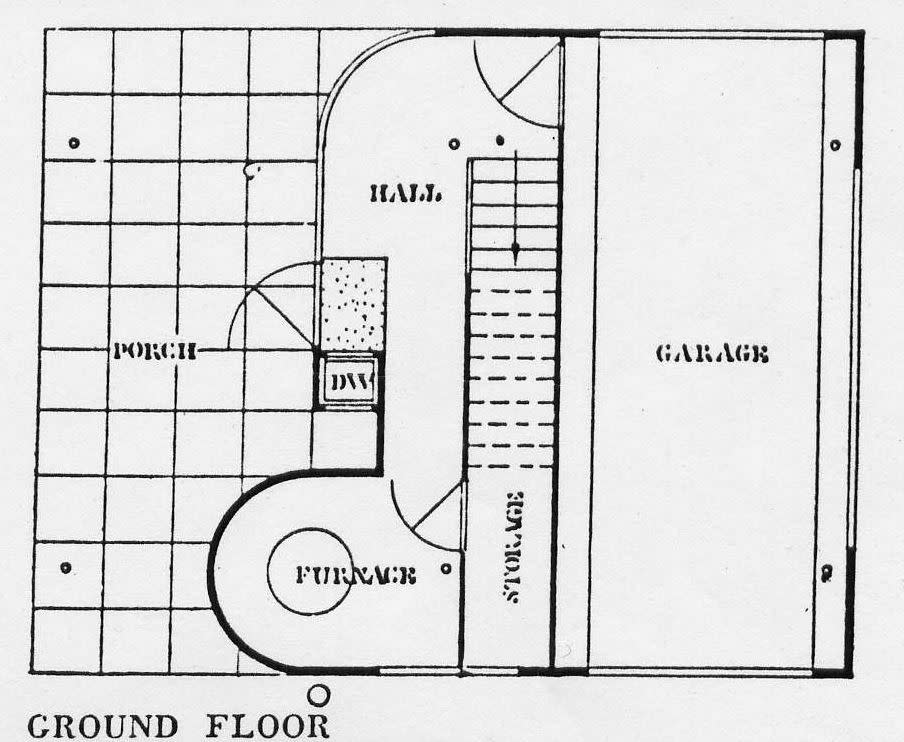

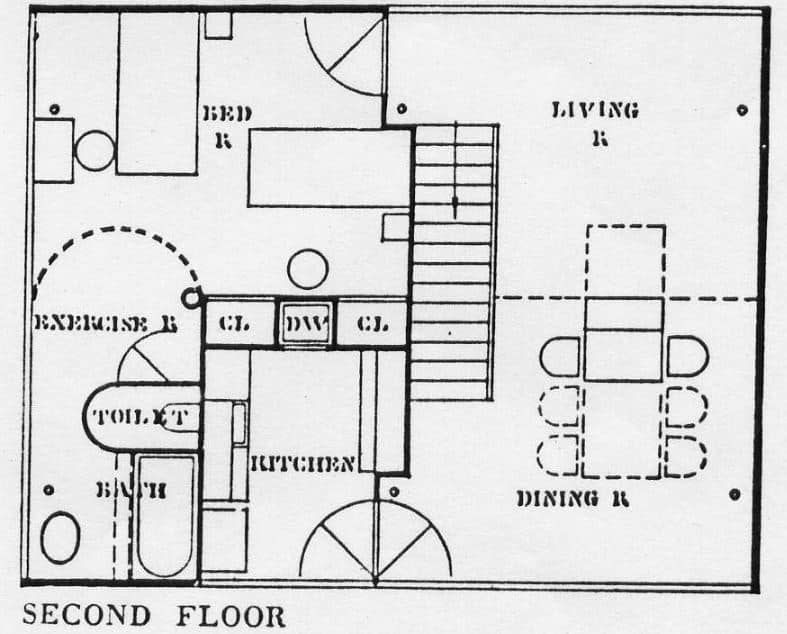

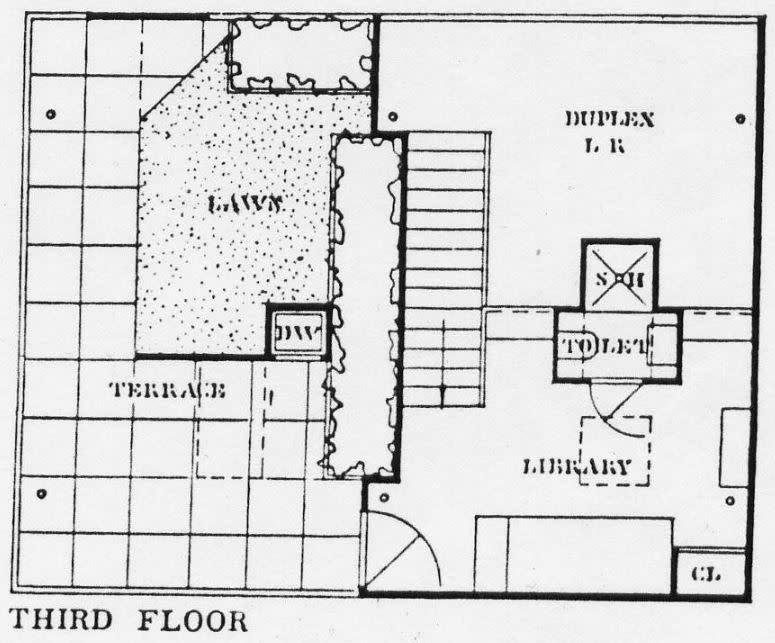

The concept was for the house to be situated near a city and inhabited by a couple. It boasted a range of amenities across its three floors.

Designed as a prototype for prefabricated housing, the Aluminaire aimed at affordability, with projections suggesting a cost of $3,200 per unit if produced in sufficient quantities (10,000 units). Echoing elements of Le Corbusier's architectural style, such as pilotis (supports that raise a building above the ground or water), ribbon windows, and a roof garden, the Aluminaire House exuded a similar aesthetic. It included a spacious combined living and dining area spanning the entire width of the house, accentuated by a double-height ceiling. Folding screens and translucent partitions added to the sense of openness, transforming individual rooms into versatile, multi-functional spaces.

"After working with Le Corbusier in Paris, my aim in life was to use permanent materials that don't require maintenance," Frey told The New York Times in 1998. "It [aluminum] was an up-and-coming material, much more durable than wood or plaster, which cracks. And it went up very quickly. The house was built in 10 days."

Neon tubes running above the windows lit the interior with dial controls, allowing the occupant to adjust the level and color of illumination. The house also featured built-in metal, glass, and rubber fixtures designed by Kocher and Frey to save space and minimize maintenance.

Ground Floor: Featured a covered porch, entrance hall, boiler room, and garage. You drive into the garage with direct access to the stair hall. Rather than backing out, you drive through the garage to exit. The construction system had six light columns of support, which allowed for the adjustment of walls to the required enclosed needs. The curved heater room area conformed to the heating unit's shape with the surrounding waking space.

Second Floor: There was a kitchen, living and dining rooms, bedroom, bathroom, and exercise room. Beds were suspended from metal cables. The living room had a view of the garden, and a special glass window occupied the entire side of the living room. A suite of air-filled rubber chairs could be deflated for easy storage. The stairway leads directly into the duplex living room, 17 feet high. The dining space was at one end of the living room. The kitchen, accessible through a double-acting door, had a compact arrangement of range, sink, refrigerator, and cabinets. A combination china cupboard and retractable dining table had legs on wheels to allow easy extension. There was also a door to a dumb waiter (noted DW on plans). The bedroom, with two closets, could be opened into an exercise space and bathroom. There was controlled privacy.

Third Floor: This floor housed a skylit library, toilet, and terrace. From the living room, the stairway continued to a library balcony. This room included a couch, closets, and cabinets. It had a ceiling of aluminum foil. It could also be used as a temporary bedroom with its own bathroom. Light and ventilation were from the skylights. A glass door opened onto the roof terrace. The covered part of the patio could be used for dining. Food was brought up from the kitchen with the dumb waiter.

Building Materials

Constructed with cutting-edge materials generously donated by national manufacturers seeking alignment with contemporary architectural trends, the Aluminaire House stands as a testament to innovation. Among the array of experimental materials utilized, aluminum and steel take center stage, playing pivotal roles in both the structure and aesthetics.

At the heart of the design, six robust five-inch aluminum pipe columns, firmly set in concrete, bear the weight of the entire edifice, proudly showcased in their exposed state. These columns serve as the backbone, supporting a meticulously crafted framework of channel girders and steel beams, which, in turn, uphold the steel floor decking and stairs with unwavering strength.

Throughout the residence, steel-framed windows usher in natural light, complemented by sleek steel-faced doors adorned with chrome trim, including the distinctive overhead doors of the drive-through garage. The exterior walls, non-load-bearing yet crucial to the architectural integrity, boast a minimalist, three-inch thick profile. Consisting of a steel frame enveloped by wood nailers and insulation board, they are clad in three-foot panels of corrugated aluminum, secured with precision using aluminum screws and washers.

Not merely functional, these aluminum panels serve a dual purpose, providing structural rigidity while reflecting the sun's rays, enhancing both practicality and aesthetic appeal. Their vertical corrugations lend strength, while the polished surface bestows upon the Aluminaire House a captivating metallic sheen, evoking the essence of modernity and sophistication.

The Aluminaire House is Relocated

When the 1931 Architectural and Allied Arts Exposition ended, architect Wallace K. Harrison purchased the building for $1,000, a Modernist architect who led the design of UN Headquarters working with Le Corbusier and others. Harrison relocated the home to his country estate on Long Island, outside New York City. It was first used as a country house, then added on to it, and later relocated elsewhere on the estate, undergoing significant changes.

In the 1940s, it was moved to Harrison’s weekend retreat, but it was structurally compromised because of construction delays. Harrison altered the house during the next decade, adding two one-story additions and enclosing the roof deck and first floor.

In 1974, Harrison sold his estate to art dealers Harold and Hester Diamond, including the Aluminaire on the property. The Diamonds sold the house to Dr. Joel Karen in 1984. The estate was on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. The following year, Dr. Karen applied for its demolition—to the chagrin of local preservationists. Although the Harrison estate was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Aluminaire House did not have the individual local listing needed to protect it.

Calls to Save The House

Calls to save Aluminaire House were made by Huntington-based preservationists and New York Times critic Paul Goldberger, who wrote the influential article "Architecture View: Icon of Modernism Poised for Extinction." They soon gained traction with a campaign by the Long Island chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Dr. Karen agreed to gift the house to the New York Institute of Technology if they would remove it from the property.

Taking notice were past dean Julio San Jose and professor Michael Schwarting of NYIT's School of Architecture and Design. They proposed moving it to its Central Islip, N.Y., site.

In 1987, San Jose and Schwarting helped NYIT secure a $131,750 grant from the New York State Office of Parks to dismantle and move the house. With the assistance of Campani, students drew the house in its original and current forms, seeking to envision it before Harrison's modifications and additions blunted the design. Next, they took it apart, moved it to Central Islip, and reconstructed it.

In 1990, the foundation received a $10,000 grant from the Alcoa Foundation of the Alcoa Aluminum company. However, funding was becoming increasingly difficult, so "Friends of Aluminaire" was established to seek matching grant funds.

In 2004, most academic programs, including the architecture program at NYIT, had moved from Central Islip to campuses in Old Westbury and Manhattan. In 2011, NYIT sold the house to the Aluminaire House Foundation.

Schwarting and Campani, who were also husband and wife, dismantled it in 2012 and stored it in New York. It then languished in a shipping container.

The Aluminaire House Finds a New Home

Michael Schwarting and Frances Campani were invited to speak at Modernism Week. During their presentation, they discussed the history and significance of the Aluminaire House and the efforts to preserve and relocate it to the Palm Springs Art Museum. Their talk provided attendees with valuable insights into the architectural legacy of the Aluminaire House and its enduring impact on modernist design.

Immediately after, the California Chapter of the Aluminaire House Foundation was registered. It was dedicated to raising funds to move the house to Palm Springs and reassemble it here for permanent display. This local committee, including Tracy Conrad, Mark Davis, Brad Dunning, Beth Edwards Harris, and William Kopelk, began raising funds to secure the permanent location for the architecturally significant house.

The foundation purchased the house in 2017 and brought it to Palm Springs.

Albert Frey Collection

The Aluminaire House is an excellent addition to the Art Museum's robust Albert Frey collection, including Frey House II (1963-64), the architect's residence until his death in 1998. Frey's connection with the museum dates back to its origin when his firm co-designed the original Palm Springs Desert Museum, and he served as a member and President of the Board of Trustees. Frey generously bequeathed his archive of drawings, personal and working papers, photographs, scrapbooks, and other documents—along with his Frey House II residence, which sits on the hillside above the museum. Albert Frey is called the father of 'Desert Modernism' and brought International Style to Palm Springs.

The Aluminaire Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit registered in California and New York. For more information or to donate, please visit aluminaire.org.

The Aluminaire House stands as more than just a piece of architecture; it symbolizes innovation, resilience, and the enduring power of design to inspire and captivate. As it takes its place among the esteemed collections of the Palm Springs Art Museum, it invites us to reflect on the past, contemplate the present, and envision the possibilities of the future. Doing so reminds us that great architecture transcends time, leaving an indelible mark on the world around us.

Palm Springs Architect Albert Frey

Great Tours: Frey House II

Palm Springs Architects and Developers

Palm Springs Self-Guided Colored Door Tour

- 8 min read

The colored doors of Palm Springs are delightful and popular. This…

Discover Palm Springs Through the Eyes of Architectural Historian Michael Stern

- 5 min read

Conventionally, buildings are constructed to shield us from the…

Mod Squad Tours: Experience Palm Springs Architecture Up Close

- 4 min read

Palm Springs is a living museum of midcentury modern architecture, and…

Complete Guide to Modernism Week 2025

- 29 min read

Thank you for joining us for Modernism Week. We look forward to seeing…

9 Midcentury Boutique Resorts: Where Timeless Design Meets Desert Luxury

- 8 min read

9 Iconic Midcentury Modern Resorts & Inns Palm Springs isn’t…