The history of Palm Springs is inseparable from the stories of its Black pioneers, men and women who arrived in the desert seeking opportunity, safety, and dignity at a time when racial discrimination shaped nearly every aspect of American life. Since the early 20th century, Black residents have helped build Palm Springs not only as a resort destination but also as a community defined by resilience, entrepreneurship, culture, and civic leadership.

Many of these pioneers lived and worked in neighborhoods such as Section 14, located on land leased from the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. While Section 14 became a vital hub for Black families and businesses, it was also the site of displacement and upheaval when redevelopment and Indian land leasing policies forced residents to relocate. Despite these injustices, Palm Springs’ Black community persisted, founding institutions, mentoring youth, shaping architecture, and influencing city politics in ways that continue to resonate today.

This Black History Month, we honor several individuals and organizations whose legacies remain deeply woven into the fabric of Palm Springs.

Note: Black History Month Events for Feb. 1 - March 1, 2026, are listed after this historical context.

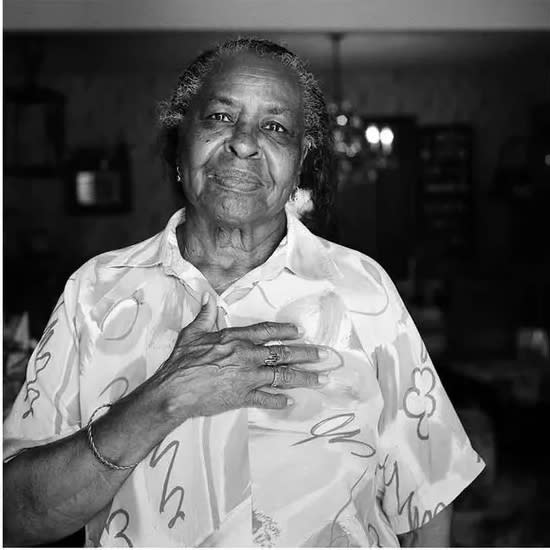

Cora Crawford

Cora Crawford’s life exemplified community leadership rooted in education, advocacy, and compassion. She moved to Palm Springs in 1951 with her husband, Samuel, and settled on Section 14 of the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation. Like many families, the Crawfords were later displaced when redevelopment plans forced residents to leave. After encountering housing discrimination in Gateway Estates, they eventually secured financing through San Gorgonio Savings and Loan and built a home in 1960, joining a growing community of former Section 14 families determined to rebuild.

In the 1960s, Crawford embraced opportunities created by the War on Poverty, becoming certified through the Head Start program. She joined the Palm Springs Child Development Center when it opened in 1964, quickly helping establish it as one of California’s most respected preschool programs. Her leadership ensured that children from working-class and underserved families received not only education, but nutrition, structure, and care.

Crawford later became the center’s director, expanding programming and hours to better serve working parents. Her influence extended far beyond the classroom. In the 1970s, she helped found the Unity Community Center, which offered sports programs, tutoring, legal assistance, and health services, creating a vital safety net for local families.

A founding member of the Palm Springs Black History Committee, Crawford also played a key role in organizing cultural events and fundraising scholarships for local students. When she passed away on April 6, 2021, at age 87, Palm Springs lost one of its most tireless advocates for children and families, and her impact endures in the generations she helped shape.

James O. Jessie

James O. Jessie, known affectionately as “Big Jess” or “Uncle James,” left an indelible mark on Palm Springs through his unwavering commitment to youth. As Director of Parks and Recreation for the City of Palm Springs, Jessie dedicated his career to mentoring at-risk children, particularly through the Desert Highland Unity Center.

Jessie believed in meeting young people where they were, offering guidance, structure, and encouragement. He coached youth baseball and softball, teaching teamwork and accountability, and helped organize the Palm Springs Black History Parade and Town Fair, annual celebrations that continue each February.

One of Jessie’s most meaningful traditions was an annual fishing trip for at-risk youth. During a trip in August 2000, a young boy fell from a boat. Without hesitation, Jessie jumped in to save him. Though the boy survived, Jessie tragically lost his life in the rescue. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Valor, and the boy he saved later named his own son James in his honor.

Today, the James O. Jessie Desert Highland Unity Center stands as a living tribute to his sacrifice and service.

James O. Jessie Desert Highland Unity Center

480 Tramview Road

Open Monday–Friday, 9 am – 6 pm

The center offers basketball, volleyball, badminton, a weight room, community rooms, and youth-focused programming designed to foster growth and connection.

Paul R. Williams

Architect Paul R. Williams (1894–1980) reshaped the American architectural landscape while breaking racial barriers. The first African American member and later Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, Williams designed nearly 2,000 homes in Los Angeles, many for clients in neighborhoods where he himself could not live.

Williams’ influence in Palm Springs is profound. Early in his career, he mentored A. Quincy Jones, and together they collaborated on several significant projects, including the Tennis Club Addition, Town & Country Center, and Romanoff’s on the Rocks (1950 - demolished).

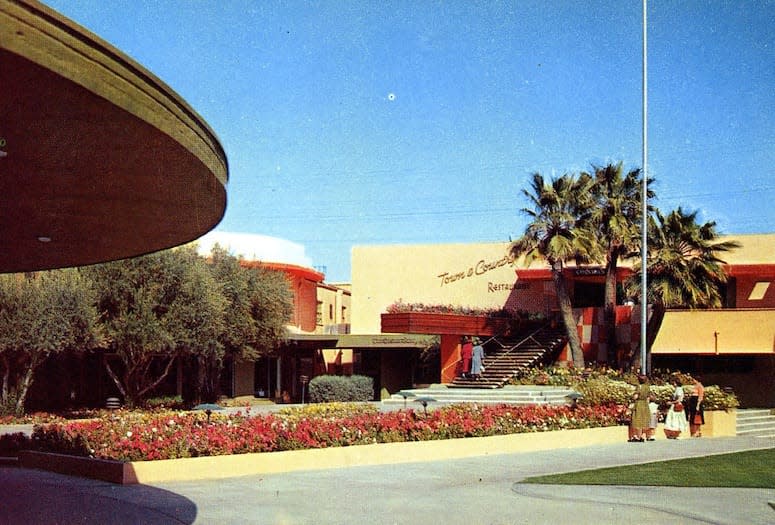

The Town & Country (1946 - 1955)

169 N Indian Canyon

A collaborative project involving Williams, Albert Frey, Donald Wexler, John Porter Clark, and others, the Town & Country Center is a landmark of desert modernism. Constructed in phases, it reflects the architectural innovation that propelled Palm Springs onto the international stage. In 2016, the site was designated a Class I Historic Site, with plans for preservation and restoration.

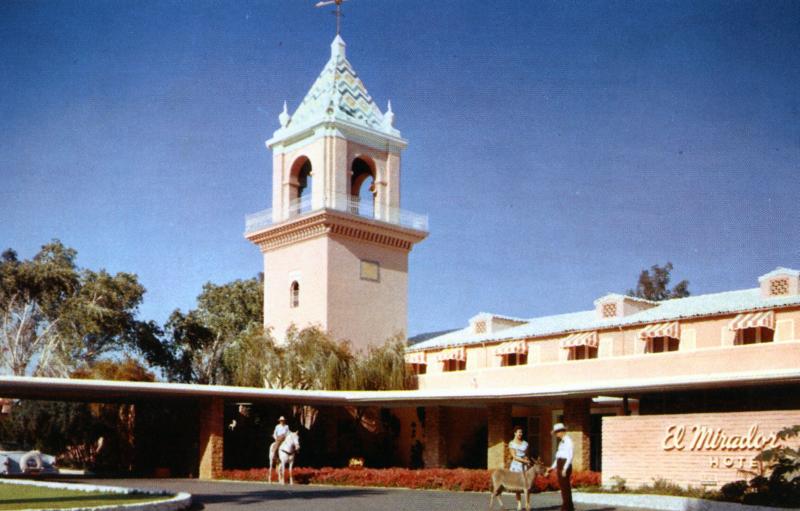

El Mirador Hotel (1952)

Williams completed a remodel of the glamorous and historic El Mirador Hotel (now the Desert Regional Hospital). It was the second luxury resort in Palm Springs, built after the popular Desert Inn, and attracted Hollywood stars, wealthy business owners, and many dignitaries. It had an Olympic-size swimming pool and Palm Springs's first 18-hole golf course.

It was later converted into Torney General Hospital, a World War II war hospital. After the war, the City of Palm Springs temporarily retained control. Various owners controlled the property until 1952, when an investment syndicate of 18, led by F. Roy Fitzgerald and Ray Ryan, purchased it for approximately $900,000 to reopen it as a luxury hotel. They engaged Paul R. Williams to renovate their property. His new design included a porte-cochere entry, cabanas, sun decks, a new pool area, and an outdoor lounge with a modernistic trellis and retractable canopy.

Palm Springs Tennis Club (1946)

It was originally built by founding pioneer Pearl McManus and was said to have one of the most beautiful pools in the country. The addition was a more sophisticated version, emphasizing solid volume, the natural wood and stone of the surrounding environment, and unpainted brick and wrap-around glass, tying the outdoors to the indoors. The addition included a new main dining room, the Bougainvillea Room, a snack bar, a cocktail lounge with a terrace for outdoor dining, and a lawn terrace for lounging and sunbathing.

In February 2018, Modernism Week, we dedicated a star for Williams on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars, joining modernist icons Albert Frey, Hugh Kaptur, Donald Wexler, E. Stewart Williams, Richard Harrison, William Krisel, William Cody, A. Quincy Jones, and Richard Neutra.

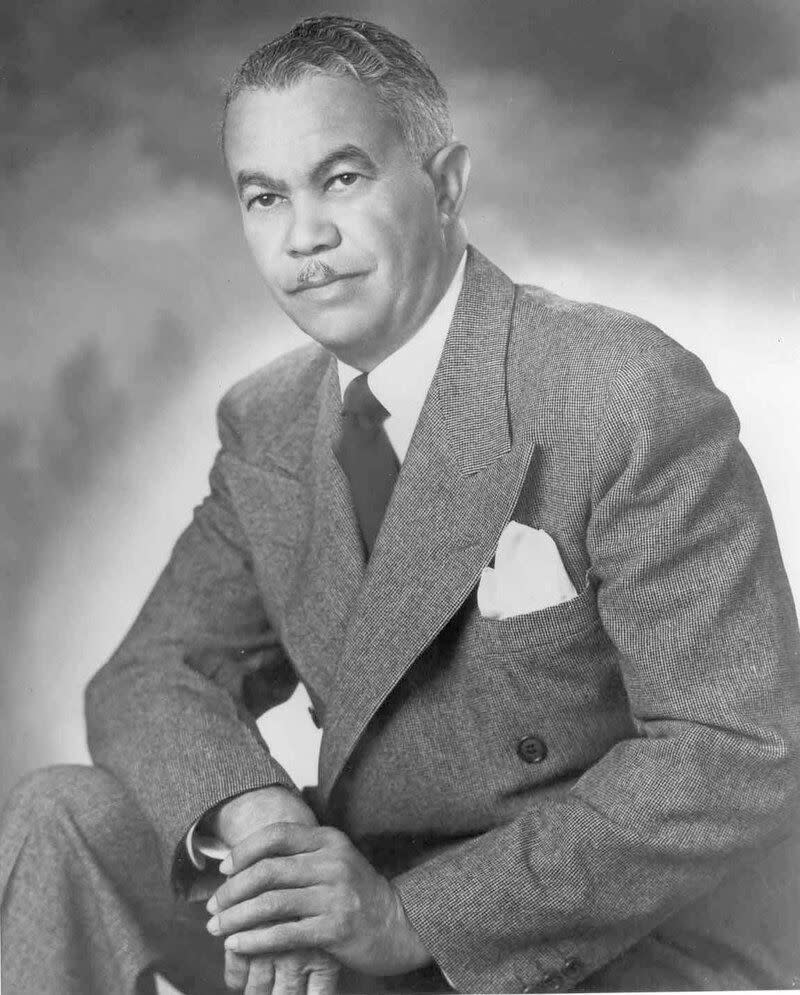

Lawrence Crossley

The Louisiana-born Lawrence L. Crossley (1899-1962) arrived in Palm Springs in 1925 and worked for Prescott T. Stevens, the owner of the El Mirador Hotel. As a leading black Palm Springs pioneer, Crossley worked his way up from chauffeur to help Stevens design and maintain the El Mirador’s golf course during the 1920s.

During the late 1930s, Crossley also built a small café (run by Mexico-born Marcus Caro) with rooms for rent on Section 14 (central downtown). In the early 1940s, Crossley began marketing a “mystery tea” based on a Native American ephedra recipe. The Palm Springs Desert Tea Co. was successful, and Crossley’s tea was sold as far away as the East Coast.

Courtesy Palm Springs Historical Society

Crossley’s Business Acumen

Crossley’s business acumen was on display in his role as the owner/watermaster of the Whitewater Mutual Water Co. (which served the north end of Palm Springs), and his ownership of the Tramview Water Co. He parlayed those investments into real estate development in Cathedral City, including the Tramview Village and Eagle Canyon Trailer Village.

Crossley advocated for better housing for the Palm Springs African American community and was publicly recognized in the early 1960s by the Los Angeles Sentinel for his efforts. Crossley, “a long-time confidant of the tribe,” also assisted in developing Native American lands and was appointed as guardian for ten members of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. He became a close friend of Chief Francisco Patencio and regularly participated in tribal rituals and programs.

During the early 1930s, Lawrence Crossley acquired approximately five acres of land south of Section 14, near the southwest corner of East Ramon Road and South Sunrise Way. This would become Crossley Court (a.k.a. Crossley Acres and Crossley Trailer Park). It is the first known example of land ownership by an African American in Palm Springs.

In September 1953, Lawrence Crossley sold the five-acre compound to the adjacent Ramon Trailer Park. He announced plans for a new subdivision two miles east of the city and a mile south of Ramon Road.

Crossley Tract

The Crossley Tract (a.k.a. Crossley Gardens and Crossley Estates) was a 77-parcel subdivision bordered by 34th Avenue on the north, Martha Street on the south, the east side of Maguerite Street on the east, and the west side of Lawrence Street on the west. The new subdivision would accommodate the displaced tenants of Crossley Court. Original plans called for relocating 32 of the 37 homes from the Ramon acreage to the new subdivision of 79 lots.

Crossley appears to have developed a partnership with the Sun-Spa Development Corporation. Sun-Spa Development's president, Al Casey, explained, “We’re particularly interested in providing immediate, low-cost housing for residents forced to move from Section 14 because of the new Indian Land Leasing Agreements.” Section 14 was being developed for commercial use, and residential leases were not renewed.

The Crossley Tract (also referenced in the early press as Crossley Estates and later Crossley Gardens) consisted of a series of modest, three-bedroom, 2.5-bath minimal traditional-style homes. Grading began in the spring of 1958, and the first home was ready for occupancy by September. In 1959, the Crossley Tract was annexed into the City of Palm Springs. Crossley died in 1961 before the project could be completed, and it faltered.

Read more: Lawrence Crossley: Palm Springs' First Black Entrepreneur and Developer

Mayor Ron Oden

Ron Oden’s leadership marked a turning point in Palm Springs’ civic history. After moving to the city in 1990 to teach sociology at College of the Desert, Oden was elected to the City Council in 1995. In 2003, he became the first African American mayor of Palm Springs and the first Black, openly gay mayor of a U.S. city.

During his tenure, Palm Springs’ tourism economy expanded dramatically, doubling the city’s budget. Oden championed diversity and inclusion through organizations such as the Palm Springs Human Rights Commission and Human Rights Task Force. His leadership helped position Palm Springs as an international symbol of equality and openness.

Oden continues to serve the community through the College of the Desert Board of Trustees and was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2019 Palm Springs Pride Honors.

Brothers of the Desert

Founded in 2017, Brothers of the Desert is a nonprofit organization supporting Black gay men and their allies across the Coachella Valley. Created in response to the isolation experienced by long-term residents, the group provides mentorship, advocacy, education, and philanthropy.

Since incorporating as a 501(c)(3) in 2020, Brothers of the Desert has awarded more than $10,000 in scholarships, hosted wellness summits, speaker series, and community events, and partnered with organizations such as Better Brothers LA, the LGBTQ Community Center of the Desert, and Coachella Valley Repertory.

In 2024, Brothers of the Desert received the Trailblazer Award from the Palm Springs Black History Committee—recognition of its growing impact and vital role in shaping a more inclusive future.

Honoring the Legacy

The Black pioneers of Palm Springs were builders in every sense, of homes, institutions, culture, and opportunity. Their stories remind us that Palm Springs’ celebrated openness and creativity were forged through perseverance in the face of exclusion. As the city continues to evolve, these legacies remain essential to understanding not just where Palm Springs has been, but where it is going.

How to Celebrate Black History Month in and Around Palm Springs

February 1 - March 1, 2026

Celebrating Black History Month is about honoring legacy, learning local stories, and participating in events that bring community and culture to life. In Palm Springs each February, residents and visitors alike can engage with history, art, performance, and community-building through a vibrant calendar of activities supported by the Palm Springs Black History Committee and local partners.

Our Voices, Our Stories: Celebrating Black Authors

Sunday, February 8 - Mizell Center, 480 S Sunrise Way, 10 am - 1 pm

- Opening reception featuring a variety of bagels, spreads, coffee, and mimosas.

- Former NFL Player RK Russell is in conversation with Lorenzo Taylor. They will be discussing Russell’s Memoir “The Yards Between Us.”

- Screenwriter and playwright Toni Ann Johnson, in conversation with Marilyn F. Solomon, will discuss her soon-to-be-released book “But Where’s Home?” (to be released February 10), a short story collection about Black life in America.

The Best Bookstore in Palm Springs will have books from featured authors available for purchase.

Free, but Registration is required.

Palm Springs Black History Tour

February 16 at 10 am - This immersive tour departs from the James O. Jessie Desert Highland Unity Center and guides participants through historic neighborhoods, landmarks, and sites connected to Black pioneers such as Lawrence Crossley and Paul R. Williams. The tour offers a powerful way to connect with local heritage on the ground. Registration begins at 9 am.

Address: 480 Tramview Road

Price: $38

You can also take a Palm Springs Black History Tour with your own tour guide throughout the year.

February Black History Show - Where History Swings, Sings & Testifies

February 20 - Sweet Baby J’ai presents a Black History Month celebration where history swings, sings, and testifies through music and storytelling. Blending live musicians, powerhouse vocals, and immersive video elements, this experience brings history off the page and onto the stage.

Hotel Zoso, 150 S Indian Canyon, 7-9 pm. Doors open at 6 pm.

Palm Springs Black History Parade & Town Fair

February 28 - the Annual City of Palm Springs Black History Month Parade & Town Fair brings vibrant culture to downtown Palm Springs with music, community vendors, food, and family-friendly activities. Anchored on Palm Canyon Drive and in Downtown Park, the parade is a joyful, inclusive celebration of history, identity, and community pride. The parade begins at 11 am

Black History Nights at the Palm Springs Art Museum

Throughout February (Thursdays), the Palm Springs Art Museum hosts engaging sessions and spotlight programs that explore Black history through art, performance, storytelling, and community dialogue. These events offer both historical context and contemporary reflection.

February 5 - Century of Black History Commemorations - In honor of 100 years of Black History Month, enjoy performances by Desert Highland drumline and drill team, and other live music performances. Small bites from Tasteful Soul Catering. Free, 5 - 8 pm. Register

Address: 101 Museum Way

Other Ways to Participate Locally

- Share and learn stories from local elders, influencers, educators, and historians about Palm Springs’ Black community.

- See the Section 14 exhibit, which is currently on display at the Agua Caliente Cultural Museum, to learn more about Palm Springs Black history as it relates to tribal land.